Salt in architecture. Between dream and reality

In the continuous search for sustainable and eco-friendly solutions, modern architecture is turning to the most unexpected materials. Among them, common salt holds a special place — a substance familiar to everyone, but rarely considered as a building element. Thanks to the work of researchers like Chilean artist and architect Mále Uribe, we are beginning to see salt not just as a seasoning, but as a key to rethinking industrial waste and creating a new, contextual architecture.

A New Philosophy of Material: Waste as a Resource

At the heart of the movement lies a powerful idea — to “rethink the life of minerals.” Mále Uribe urges us to look at natural resources not only through the lens of their economic value but also to see their cultural significance and hidden potential. This approach becomes particularly relevant when considering the shocking inefficiency of the modern mining industry.

The facts speak for themselves:

- During copper extraction, only 3% of the mined rock becomes valuable concentrate.

- In lithium extraction from the brines of the Atacama Desert, its concentration is less than 2%.

The remaining 97-98% — giant volumes of salts, sand, and gravel — are written off as waste, forming artificial mountains and harming fragile ecosystems. “Minerals are never waste,” Uribe asserts, “rather, we position them as waste.” It is in these millions of tons of “useless” rock that she sees a most valuable resource for the construction industry.

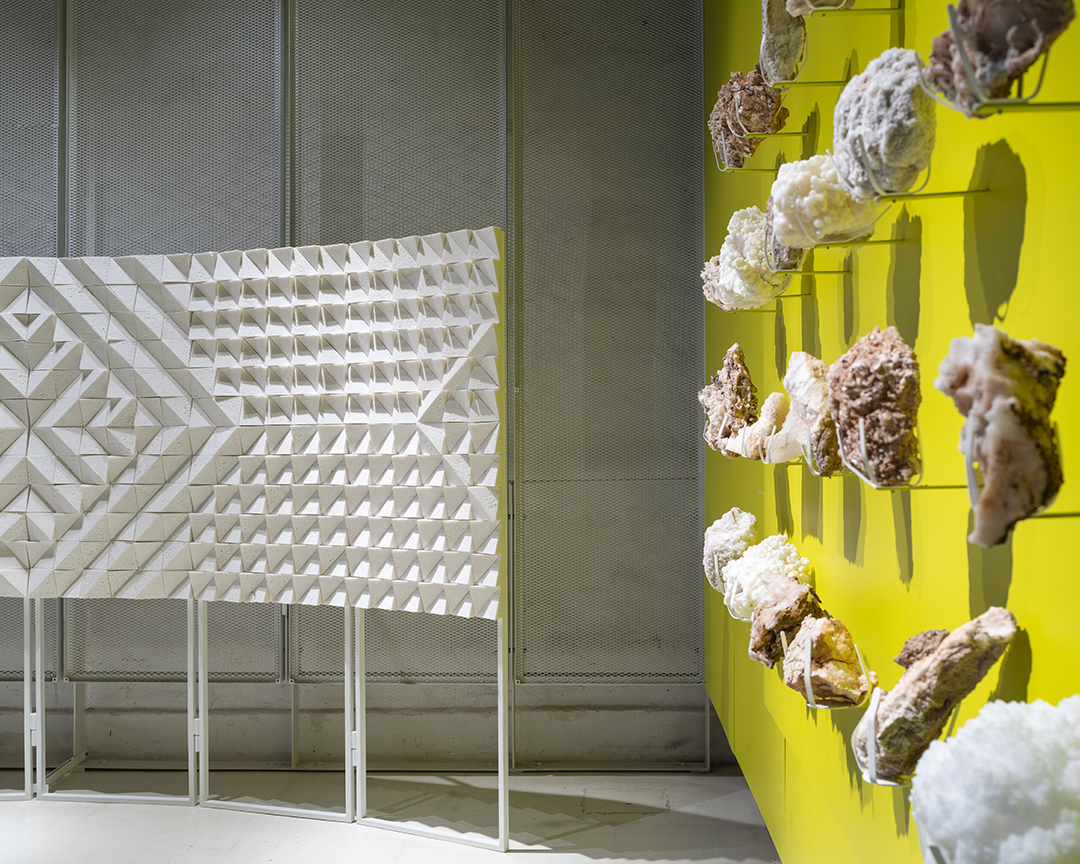

As a material, salt has a number of attractive properties: it is affordable, fire-resistant, a natural antiseptic, and also has unique aesthetic qualities, reflecting and softly diffusing light. Historical examples, like the “Palacio de la Sal” salt hotel in Bolivia, prove that the idea itself is not new. In her projects, such as “Salt Imaginaries,” Uribe goes further, experimenting with crystallization, compaction, and heat treatment to create unique structures, tiles, and art objects from the waste of salt extraction.

A Sober Assessment: Fundamental Obstacles

However, before we start designing salt cities, a sober engineering assessment is necessary. Despite all its potential, salt has fundamental limitations that sharply narrow its scope of application.

- The main enemy — water. This is an insurmountable obstacle. Salt is hygroscopic (it absorbs moisture from the air) and completely dissolves in water. In any climate other than extremely arid, a salt building will be subject to erosion from rain, fog, and high humidity. This makes it practically unusable for exterior structures in most regions of the world.

- Low structural strength. Salt is a brittle material that cannot bear heavy loads. It is impossible to build multi-story or complex engineered buildings from it. Its role is limited to non-load-bearing walls, partitions, and finishes.

- Aggressive corrosion. Salt is a powerful oxidizing agent. Any contact with steel reinforcement, fasteners, or a metal frame will lead to their rapid destruction. This requires the use of expensive composite materials or stainless alloys, which negates the economic advantage of salt.

- Lack of standards. The conservative construction industry operates on the basis of strict codes and regulations. For salt, as for most unconventional materials, such standards do not exist, making its use in capital construction practically impossible today.

A Promising Niche, Not a Global Revolution

So where is the real future of salt in architecture? It is not in replacing concrete and brick, but in smart, highly specialized niches.

- A local solution for local problems. The technology's greatest strength — is the utilization of industrial waste. In arid mining regions like Chile or Bolivia, processing salt tailings into local building materials — is a brilliant, economically and ecologically sound solution.

- Interior design and finishing. Indoors, where the material is protected from the elements, its potential is fully realized. Its antibacterial properties, unique aesthetics, and fire resistance make salt an ideal candidate for decorative panels, tiles, and partitions in spas, restaurants, galleries, and residential spaces.

- Art and temporary architecture. Salt's ability to self-crystallize — is a gift for artists and designers. Temporary pavilions, art objects, and installations that “live” and change over time — provide an exciting field for experimentation.

Ultimately, the main value of the research by Mále Uribe and her peers — is not a recipe for a salt house. It is a fundamental shift in thinking: a call to see vast resources, beauty, and potential where most see only industrial waste. And this lesson is far more important for the future of architecture than any single building material.